The Jurisprudence and Procedural Framework of Marriage Dissolution in Canada: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Divorce Act and Provincial Practice

Part I: The Constitutional and Statutory Architecture of Divorce

The dissolution of marriage in Canada operates within a complex matrix of federal substantive law and provincial procedural regulation. This duality stems from the Constitution Act, 1867, which assigns “Marriage and Divorce” to the exclusive legislative authority of the Federal Parliament under Section 91(26), while assigning the “Administration of Justice” and “Property and Civil Rights” to the provinces. Consequently, the substantive grounds for divorce are uniform across the country, governed by the federal Divorce Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. 3 (2nd Supp.), while the mechanisms for obtaining that relief—the forms, filings, and court processes—are dictated by provincial rules, such as Ontario’s Family Law Rules, O. Reg. 114/99.1

This report provides an exhaustive examination of the legal regime governing the breakdown of marriage in Canada. It analyzes the statutory “breakdown” test, the rigorous evidentiary requirements for establishing separation, the vestigial but operational fault-based grounds, and the procedural gauntlet litigants must navigate to obtain a divorce order.

1.1 The Singular Ground: Breakdown of Marriage

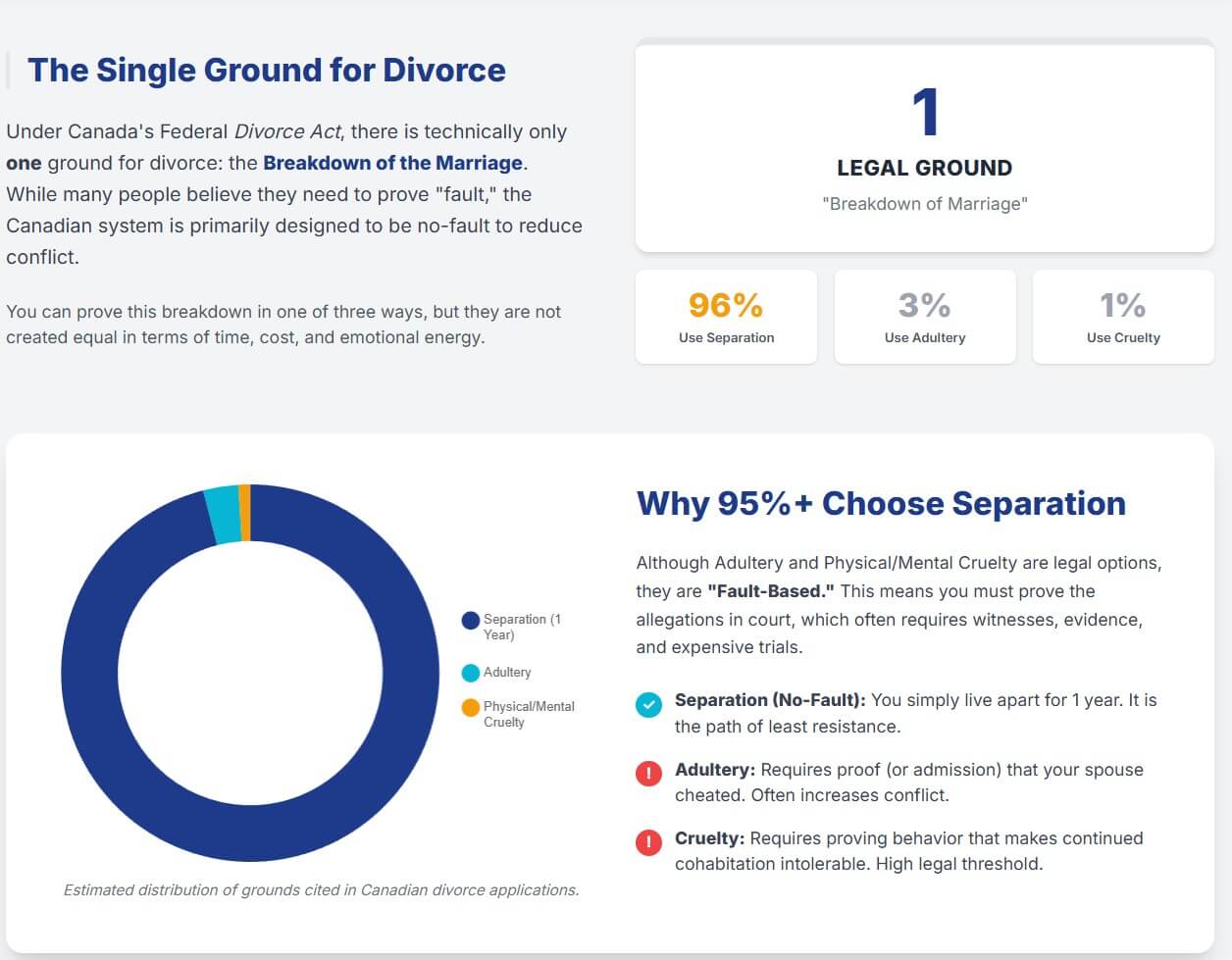

A pervasive misconception in the public sphere is that Canada has multiple grounds for divorce. Legally, under Section 8(1) of the Divorce Act, there is only one ground: the breakdown of the marriage. The statute explicitly states that a court of competent jurisdiction may grant a divorce to a spouse or spouses on the ground that there has been a breakdown of their marriage.4

While the ground is singular, the Divorce Act provides three distinct evidentiary routes—often colloquially referred to as “grounds”—to prove that this breakdown has occurred. Section 8(2) stipulates that the breakdown of a marriage is established only if:

- The spouses have lived separate and apart for at least one year immediately preceding the determination of the divorce proceeding and were living separate and apart at the commencement of the proceeding; OR

- The spouse against whom the divorce proceeding is brought has, since the celebration of the marriage:

- Committed adultery; OR

- Treated the other spouse with physical or mental cruelty of such a kind as to render intolerable the continued cohabitation of the spouses.4

This legislative structure creates a “no-fault” regime (via separation) alongside a “fault” regime (via adultery or cruelty). However, the vast majority of Canadian divorces proceed on the basis of separation, as it avoids the acrimony, cost, and evidentiary burdens associated with proving matrimonial misconduct.

1.2 Jurisdiction and the “Habitual Residence” Test

Before a court can entertain an application for divorce, it must possess subject-matter jurisdiction. The mere presence of a marriage certificate is insufficient; the court must have a connection to the parties. Section 3(1) of the Divorce Act establishes that a court in a province has jurisdiction to hear and determine a divorce proceeding if either spouse has been “habitually resident” in that province for at least one year immediately preceding the commencement of the proceeding.6

1.2.1 Statutory Interpretation of “Habitually Resident”

The requirement for habitual residence prevents “forum shopping,” where litigants might otherwise seek out jurisdictions with more favorable procedural rules or shorter wait times. The term “habitually resident” implies a physical presence coupled with a settled intention to reside.

- Mobility Considerations: This rule has significant implications for separated spouses who relocate. If a spouse moves from Ontario to Alberta immediately after separation, they cannot commence a divorce application in Alberta until they have resided there for a full year. They may, however, file in Ontario if the other spouse remains there, or wait for the Ontario-based spouse to file.7

- The Civil Marriage Act Exception: A lacuna existed for non-resident couples who married in Canada (often same-sex couples from jurisdictions where such marriages are not recognized) but could not divorce in their home country. The Civil Marriage Act now permits the dissolution of a marriage in the province of solemnization if the parties are not residents of Canada and cannot obtain a divorce in the country where they reside.7

1.2.2 The Transfer of Proceedings

Where divorce proceedings are commenced in two different provinces on the same day, the Federal Court may determine which court retains jurisdiction, although typically, the first validly filed application takes precedence. The Divorce Act prioritizes the connection of the child to the jurisdiction in matters involving parenting orders, but for the divorce itself, the residency of the spouses is the controlling factor.6

Part II: The No-Fault Regime: Separation as the Primary Indicator

The “separate and apart” provision is the cornerstone of modern Canadian divorce law. It reflects a legislative policy that if a couple has lived apart for a sustained period, the marriage is irretrievably broken, regardless of who “caused” the split.

2.1 The Temporal Requirement: The One-Year Rule

Section 8(2)(a) requires that spouses live separate and apart for at least one year. This creates two distinct timelines that legal practitioners must manage:

- Commencement of Application: An application for divorce based on separation can be filed at any time after the separation has occurred. The litigant does not need to wait for the year to elapse before initiating the court process.5

- Determination of Proceeding: The court cannot grant the divorce judgment until the one-year period is complete.5

Strategic Implication: Filing immediately after separation allows parties to access the court system to resolve corollary relief—such as child support, spousal support, and property division—while the “divorce clock” ticks. By the time the financial and parenting issues are resolved (which often takes more than a year), the ground for divorce will have ripened.

2.2 Defining “Separate and Apart”: The Oswell and Greaves Jurisprudence

The concept of living “separate and apart” is a term of art. It involves both a physical element (factum) and a mental element (animus). The jurisprudence, particularly the leading cases of Oswell v. Oswell (1990) and Greaves v. Greaves (2004), establishes that physical separation alone is insufficient without the intent to end the marriage, and conversely, that physical separation is not strictly required if the “matrimonial consortium” has ended.8

2.2.1 The Intent to Separate (Animus Separandi)

Section 8(3)(a) of the Act clarifies that spouses are deemed to have lived separate and apart if they lived apart and either of them had the intention to live separate and apart.4 This confirms that separation can be a unilateral act. A spouse does not need the consent of their partner to separate; they merely need to manifest the intent to end the relationship. The decision to separate does not require a “meeting of the minds”; it can be made by one party over the objection of the other.10

2.3 Separation Under the Same Roof

Economic realities, particularly in high-cost housing markets like Ontario, often force separated couples to continue residing in the same matrimonial home. The law recognizes this reality. Litigants can legally “live separate and apart under the same roof,” provided they can prove that they have withdrawn from the matrimonial partnership.11

This state of affairs places a higher evidentiary burden on the applicant. The court requires “clear and convincing evidence” that the couple is living as two independent individuals rather than as a married unit. The Oswell and Greaves line of cases provides a non-exhaustive list of factors—indicia of separation—that courts analyze:

| Category of Conduct | Indicia of Separation (Under the Same Roof) | Indicia of Continued Cohabitation |

| Physical Occupancy | Occupying separate bedrooms; established privacy boundaries within the home.11 | Sharing a bed; unrestricted access to each other’s private spaces. |

| Sexual Relations | Complete cessation of sexual intimacy.11 | Continued sexual relations (though not determinative, it is a strong factor). |

| Domestic Services | Ceasing to perform household chores for the other (e.g., separate laundry, separate cleaning duties).8 | Continuing to cook family meals, clean the other’s clothes, or maintain the home jointly. |

| Meal Patterns | Eating meals separately or at different times; purchasing groceries individually.8 | Regular family dinners; shared grocery shopping and preparation. |

| Social Activities | attending social functions (weddings, parties) alone; telling friends/family of the separation.8 | Attending events as a couple; presenting to the community as a unified entity. |

| Communication | Limiting conversation to logistical matters (bills, children); absence of “family problem” discussions.8 | Confiding in each other; discussing personal or emotional matters. |

| Finances | Separating bank accounts; ceasing joint contributions to savings; filing taxes as “separated”.12 | Joint bank accounts; shared credit cards; financial interdependence. |

Synthesis of Factors: No single factor is determinative. In Greaves v. Greaves, the court emphasized a “global analysis” of the unique realities of the relationship. For instance, if a couple maintained separate bedrooms for years during the marriage due to snoring or scheduling, continuing that arrangement does not prove separation. There must be a palpable change in the dynamic that signifies a withdrawal from the matrimonial obligation.9

2.4 Reconciliation and the 90-Day Rule

The Divorce Act is designed to support the institution of marriage where possible. To prevent the legal regime from discouraging reconciliation attempts (out of fear of “resetting the clock”), Section 8(3)(b)(ii) includes a specific saving provision.

The period of separation is not interrupted by a resumption of cohabitation if:

- The primary purpose of the cohabitation is reconciliation; AND

- The period or periods of cohabitation do not total more than 90 days.4

This allows spouses to “test” their relationship. They can move back in together, attempt to work things out, and if it fails within three months, the original separation date stands.

- Cumulative Calculation: The 90 days need not be consecutive. A couple could reconcile for 30 days, separate, and reconcile for another 40 days. As long as the sum is 90 days or less, the separation is deemed continuous.15

- Exceeding the Limit: If the reconciliation attempt lasts 91 days, the separation clock resets to zero, and the parties must wait a full year from the new separation date before a divorce can be granted.7

Part III: The Fault-Based Grounds: Adultery and Cruelty

While less common, the fault-based grounds remain available and permit an application for divorce to be brought immediately, without the one-year waiting period. However, the procedural complexity often makes these grounds unattractive unless there is a specific urgency (e.g., safety concerns or urgent remarriage plans).

3.1 Adultery

Section 8(2)(b)(i) permits divorce where the respondent has committed adultery.

- Definition: Adultery is voluntary sexual intercourse with a person other than the spouse. It encompasses acts with same-sex partners.16

- Standard of Proof: The standard is the civil standard—balance of probabilities—but the evidence must be robust. Mere suspicion or “emotional affairs” (sexting without contact) generally do not satisfy the statutory definition.17

- The “Innocent Party” Rule: A spouse cannot seek a divorce based on their own adultery. Only the “innocent” spouse can file. If both have committed adultery, they can cross-claim, but one cannot rely on their own misconduct to secure the divorce.17

3.1.1 The Procedural Mechanism of Proving Adultery

In an uncontested divorce, adultery is rarely proven by hiring private investigators to testify. Instead, it is typically proven via Affidavit. The respondent (the spouse who committed adultery) must be willing to swear an affidavit admitting to the act.

- Naming the Co-Respondent: Under Ontario’s Family Law Rule 36(3), the third party involved in the adultery need not be named. However, if they are named in the application, they effectively become a respondent and must be served with the documents, granting them all rights of a party. This creates a disincentive to name the third party, keeping the proceedings cleaner and more private.19

- Condonation: Adultery acts as a ground only if it has not been “condoned” (forgiven). If the innocent spouse takes the cheating spouse back and resumes marital life for more than 90 days, the ground is lost.16

3.2 Physical and Mental Cruelty

Section 8(2)(b)(ii) defines cruelty as treatment that renders “intolerable the continued cohabitation of the spouses.”

- The Test: This is a subjective-objective test. The court asks whether this conduct by this respondent towards this applicant was of such a nature that this applicant could not reasonably be expected to live with the respondent.5

- Distinction from Incompatibility: Cruelty requires “grave and weighty” conduct. It is distinct from the normal “wear and tear” of married life, incompatibility, or simple arguments.

- Mental Cruelty: This is harder to prove than physical violence. It often requires medical or psychological evidence showing that the respondent’s behavior caused actual injury to the applicant’s health or mental state.

Practical Insight: Filing for divorce on cruelty grounds requires the applicant to detail the abuse in a public court file (the Affidavit for Divorce). This often inflames conflict, potentially damaging the prospects of settling corollary issues like parenting and support. Consequently, counsel often advise proceeding on the separation ground unless the divorce order is required immediately for safety or immigration reasons.11

Part IV: Bars to Divorce and Judicial Duties

Even when a ground is established, the Divorce Act imposes affirmative duties on the court to refuse the divorce in specific circumstances. These are known as “bars.”

4.1 Collusion (Section 11(1)(a))

Collusion is an absolute bar. The court must satisfy itself that there has been no collusion in relation to the application.

- Definition: Collusion includes an agreement or conspiracy to fabricate or suppress evidence to deceive the court (e.g., agreeing to lie about the date of separation to speed up the process, or fabricating an affair).20

- Excluded Agreements: Importantly, Section 11(4) clarifies that collusion does not include an agreement to separate, to divide property, or to regulate financial support. Cooperation is encouraged; deception is prohibited.20

4.2 Connivance and Condonation (Section 11(1)(c))

These are bars applicable only to fault-based grounds.

- Connivance: Encouraging the spouse to commit the matrimonial offense (e.g., entrapment).

- Condonation: Forgiving the offense and reinstating the marriage.

- Public Interest Exception: Unlike collusion, these bars are not absolute. The court may still grant the divorce if it is of the opinion that the “public interest would be better served by granting the divorce” despite the condonation or connivance.20

4.3 The Protection of Children: Section 11(1)(b)

The most frequently litigated “bar” in modern practice is Section 11(1)(b), which mandates that the court satisfy itself that “reasonable arrangements have been made for the support of any children of the marriage, having regard to the applicable guidelines.”

- The “Stay” Power: If the court finds the arrangements unreasonable (typically, if child support is below the Federal Child Support Guidelines amount without a valid explanation), it must stay the granting of the divorce until proper arrangements are made.5

- Judicial Oversight: This transforms the judge into an active inquisitor. Even in an uncontested joint divorce where both parents agree to waive support, the judge will reject the application. The parents’ agreement cannot override the child’s right to support.22 Litigants must file detailed Financial Statements or income evidence (Notices of Assessment) to prove the support amount is compliant.

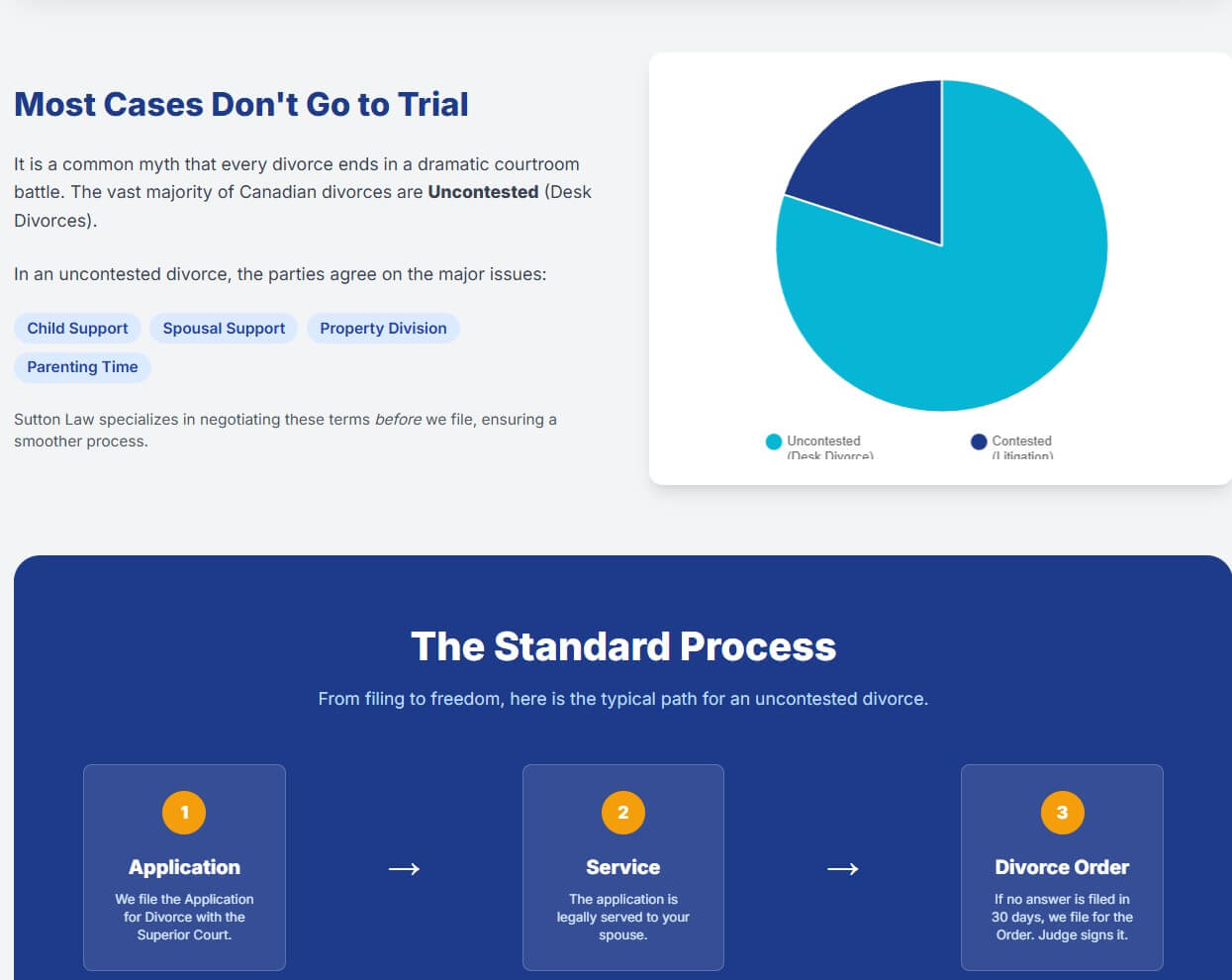

Part V: Procedural Framework in Ontario: The Family Law Rules

While the Divorce Act is federal, the procedure is provincial. In Ontario, the Family Law Rules (O. Reg. 114/99) govern every step. The process is document-heavy and strictly regulated.

5.1 Initiating the Application

There are three primary vehicles for commencing a divorce in Ontario:

| Application Type | Form | Usage Scenarios |

| Simple Application | Form 8A | Used when the only claim is for divorce. No property, support, or parenting claims are made (usually because they are already settled or not pursued).23 |

| Joint Application | Form 8A | Both spouses sign as Co-Applicants. Indicates total agreement on divorce and all corollary issues. Faster processing as no service is required.23 |

| General Application | Form 8 | Used when seeking divorce plus other relief (e.g., “Divorce + $50,000 Equalization Payment + Spousal Support”). Initiates a contested or complex matter.23 |

5.2 The Paperwork Ecosystem

A successful divorce file requires a precise constellation of documents. Missing any one of these results in administrative rejection.

- Form 8A (Application): The originating process. Must state the ground (separation) and date.

- Original Marriage Certificate: Section 36(4) of the Rules strictly requires the filing of the marriage certificate or marriage registration certificate.

- The “Original” Rule: Photocopies are generally rejected unless the court grants leave based on an affidavit explaining why the original cannot be obtained.19

- Foreign Marriages: If married abroad, the foreign certificate is required. If not in English/French, a certified translation is mandatory.

- Form 6B (Affidavit of Service): Proof that the Respondent received the Application.

- Form 36 (Affidavit for Divorce): This is the core evidence. It is sworn after the one-year separation period is complete. It confirms:

- The facts in the application remain true.

- No reconciliation has occurred.

- Residency requirements are met.

- No collusion/bars exist.

- Child support arrangements are proper.19

- Form 35.1 (Affidavit in Support of Claim for Custody/Parenting): If there are children, this form details their care, residence, and any history of family violence, consistent with the 2021 Divorce Act amendments focusing on the “best interests of the child”.23

- Form 25A (Divorce Order): The draft judgment prepared for the judge’s signature.23

5.3 The Service of Documents (Rule 6)

Service is the mechanism of due process. Rule 6 of the Family Law Rules sets out a hierarchy of delivery methods.

- Initiating Documents (Special Service): The Application (Form 8A) generally requires personal service on the Respondent.

- Prohibition: The Applicant cannot serve the documents themselves. They must utilize a third party (friend, family member over 18, or professional process server).27

- Process: The server hands the envelope to the Respondent. If the Respondent refuses to take it, dropping it at their feet after identifying the document constitutes valid service.

- Substituted Service: If the Respondent evades service or cannot be located, the Applicant cannot simply email them. They must file a motion (Form 14B) asking the court for an order permitting “substituted service” (e.g., via email, Facebook, or serving a parent). The Applicant must prove they made diligent efforts to locate the person first.29

- Service in Joint Applications: In a joint application, service is not required because both parties signed the initiating document.26

5.4 Financial Implications: Court Fees

The cost of divorce in Ontario includes mandatory filing fees payable to the Minister of Finance.

| Step | Fee (Approximate) | Description |

| Filing Application | ~$224.00 | Paid when Form 8A is issued by the court clerk.30 |

| Filing Answer | ~$171.00 | Paid by the Respondent if they wish to contest the divorce or make their own claims.32 |

| Setting Down | ~$445.00 | Paid when filing the Affidavit for Divorce (Form 36) to request the judge’s review.30 |

| Total Standard Fees | ~$669.00 | The baseline administrative cost for an uncontested divorce. |

Note: Fee waivers are available for litigants who meet low-income eligibility thresholds.33

5.5 Timelines and the “31 Days” Rule

The timeline for divorce is governed by both statutory waiting periods and administrative processing times.

- Response Period: Once served, the Respondent has 30 days to file an Answer (Rule 10). If served outside Canada/USA, this extends to 60 days.34

- Noting in Default: If no Answer is filed after 30 days, the Applicant can proceed on an uncontested basis.

- Judicial Review: The file is passed to a judge. In many Ontario jurisdictions (e.g., Brampton, Toronto), backlogs can cause this review to take 4 to 6 months.35

- Effect of Divorce (Section 12): Once the judge signs the Divorce Order, the parties are not yet divorced. Section 12 of the Act dictates that the divorce takes effect on the 31st day after the day the judgment is rendered.21

- Rationale: This 31-day window is the appeal period.

- Exception: The court can grant an earlier effective date (waiving the 31 days) in “special circumstances” (e.g., urgent need to remarry due to terminal illness), provided the parties agree not to appeal.21

- Certificate of Divorce: Only after the 31 days have elapsed can the parties obtain the final Certificate of Divorce (Form 36B), which is required to apply for a new marriage license.19

Part VI: Common Pitfalls and Rejection Reasons

The administrative rejection rate for divorce applications in the Superior Court of Justice is high. Litigants and junior counsel frequently encounter the following hurdles:

6.1 The “Wet Ink” vs. Electronic Signature Confusion

While Ontario courts moved toward electronic filing (CaseLines/JSO) post-2020, strict rules remain regarding affidavits. Affidavits must be commissioned properly. If a virtual commissioning process (video call) was used, the jurat (signature block) must specifically state that the remote commissioning regulation was followed. Failure to include this specific wording leads to rejection.36

6.2 Naming Conventions and The Continuing Record

The Family Law Rules (Rule 9) require a “Continuing Record”—a formal dossier of the case. Documents filed electronically must follow precise naming conventions (e.g., “Application Form 8A – Applicant – Smith – 12-JAN-2025”). Deviating from this format, or failing to update the Table of Contents, results in the clerk refusing to accept the filing.37

6.3 Child Support Calculation Errors

As established in Part IV, Section 11(1)(b) is a rigid gatekeeper. Common reasons for rejection include:

- Failing to attach the most recent Notice of Assessment from the CRA.

- Proposing a child support amount that deviates from the Guidelines without a detailed explanation in the Affidavit (e.g., “We agreed to less because I took the debt” is often insufficient without showing the arrangement benefits the child).22

- Failing to account for “Section 7” special expenses (daycare, medical) in the order.22

6.4 Missing Original Marriage Certificate

Submitting a photocopy of the marriage certificate without a court order permitting it is an automatic rejection. If the certificate is lost, the applicant must delay the divorce to order a new one from the Registrar General.25

Part VII: Conclusion

The landscape of divorce in Canada is characterized by a dichotomy: a streamlined, no-fault substantive regime encased in a rigorous, document-intensive procedural framework. While the “breakdown of marriage” via one-year separation is the nearly universal ground, the process of formalizing that breakdown requires strict adherence to federal evidence laws and provincial rules of court.

For the legal practitioner, the focus is rarely on proving the why of the divorce—as fault is largely irrelevant to the outcome—but on ensuring the how satisfies the court’s administrative and protective duties. The rigorous application of the Oswell factors for separation under the same roof, the strict s. 11(1)(b) review of child support, and the mandatory service protocols of Rule 6 serve as the primary checkpoints. Success in this domain requires not just knowledge of the Divorce Act, but a mastery of the forms, fees, and filing protocols that operationalize it.

Summary of Key Legislative Provisions

| Provision | Statute | Legal Principle |

| s. 8(1) | Divorce Act | Establishes “Breakdown of Marriage” as the sole ground. |

| s. 8(2)(a) | Divorce Act | Defines breakdown as 1-year separation. |

| s. 3(1) | Divorce Act | “Habitually Resident” (1 year) jurisdiction rule. |

| s. 11(1)(b) | Divorce Act | Duty to stay divorce if child support is inadequate. |

| s. 8(3)(b)(ii) | Divorce Act | 90-day reconciliation tolling provision. |

| Rule 6 | Family Law Rules | Governance of Service of Documents (Personal vs. Substituted). |

| Rule 36 | Family Law Rules | Specific procedures for Divorce Affidavits and Certificates. |

| s. 12 | Divorce Act | The 31-day delay before the divorce takes effect. |

Works cited

- Divorce Act ( RSC , 1985, c. 3 (2nd Supp.)) – Justice Laws Website, accessed January 23, 2026, https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/d-3.4/

- Guide to procedures in family court | ontario.ca, accessed January 23, 2026, https://www.ontario.ca/document/guide-procedures-family-court

- O. Reg. 114/99: FAMILY LAW RULES” – Ontario.ca, accessed January 23, 2026, https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/990114/v36

- Divorce Act ( RSC , 1985, c. 3 (2nd Supp.)) – Justice Laws Website, accessed January 23, 2026, https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/D-3.4/section-8.html

- Fact Sheet – Divorce – Department of Justice Canada, accessed January 23, 2026, https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/fl-df/fact4-fiches4.html

- Divorce Act ( RSC , 1985, c. 3 (2nd Supp.) – Justice Laws Website, accessed January 23, 2026, https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/d-3.4/fulltext.html

- How to Apply for a Divorce – Department of Justice Canada, accessed January 23, 2026, https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/fl-df/divorce/app.html

- When does a couple actually separate after they say they are separated? – Shankar Law Office, accessed January 23, 2026